Chinese Themes

in American Art

Chinese Themes in Early American Art

—Theodore Wores’s art helped to form a positive image of Chinese people in 19th century America. This article is an in-depth analysis of American artist Theodore Wores' contribution to the rise of, coinage and extension of Chinese subject matters in American art history. It is also a rare attempt to represent the complete set of his artworks on Chinese themes. The main challenge to bring this work to the art world, is that the location of the majority of his Asian-inspired canvases remains unknown, with only photographic records of the pieces in existence

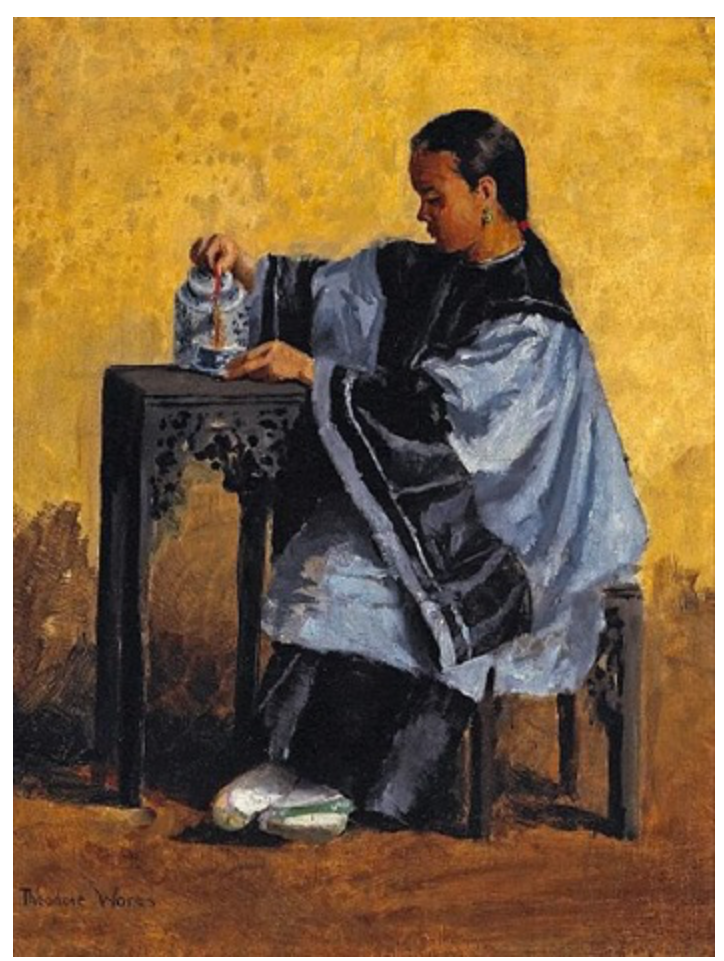

In the first images, we see colourful, realistic and detailed depictions of Chinese people in their folk attires in typically Chinese atmosphere, at their traditional dining table dancing and singing (Pic. 1), celebrating New Year (Pic.2), pouring Chinese tea (Pic.3). Engaged in various actions related to their customs and origin- all of these poignant oil paintings are created by but an American artist at the end of the 19th century. Theodore Wores (August 1, 1859 – September 11, 1939), employed the manners and technique of the European oil paintings of his time, including linear perspective, foreshortening, contrast of light and shadow, reflection of the volume of figures and objects, tints and shades, etc. Moreover, the artist had never been to China, his Chinese protagonists are the inhabitants of San Francisco’s Chinatown.

(Pic 1) Photograph of a painting by Theodore Wores of a standing warrior with musicians in the background, 19th century, California Historical Society

(Pic 2) Theodore Wores, “New Year’s Day in San Francisco’s Chinatown”, 1881, oil on canvas

So we might ask, why was the painter obsessed with the Asian themes? And, why did Chinese motifs particularly play a significant role in his career?

1. Influences of Wores childhood

Wores grew up in San Francisco, Northern California. He came to know San Francisco’s Chinatown (establishment in 1848, it has been highly important and influential in the history and culture of ethnic Chinese immigrants in North America) as a child while walking home from his father’s hat business store through the bustling Asian community quarters.

2. Teaching experience in Asian headquarters

Wores was one of the first American artists to venture into the city’s Chinatown. He is marked as a “pioneer in the exploration of Chinatown subject matter”. While creating his famous paintings of the Asian quarter in 1884, he also taught Western art to a small, enthusiastic group of 12 Chinese students.

3. Artistic tendencies of his time (involving Japanese and Chinese objects in the compositions)

According to the biographers, Wores’s friends included artists, such as William Merritt Chase (see “Spring Flowers (Peonies)”, 1889. Pastel on paper, prepared with a tan ground, and wrapped with canvas around a wooden strainer, 48 x 48 inches. Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1992.32) who from time to time were turning their brushes towards Asian themes, among them Chinese porcelain, Japanese kimono, partly inspired by French school of Orientalism and Aestheticians. Thus, the entourage and surroundings made a positive ground for growing interest in Asian culture, and Chinese, in particular.

(Pic 3) Theodor Wores, “A Chinese beauty Pouring tea”, 19th century, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 in. (50.8 x 40.6 cm.)

4. Positive responses of museums, connoisseurs and audience

An American local artist noticed Wores’s talent and encouraged him to attend the Royal Academy in Munich. After six years in Munich, Wores returned to San Francisco eager for new subjects to paint and turning his gaze to Chinatown. Among the early Chinatown canvases “Chinese Candy Seller” (Pic.4) was sold to the E.B. Crocker collection, “The Chinese Shop” to Sir Thomas Hasketh. The latter’s wife commented on the picture, saying "so realistic you can smell it." His series brought forth orders from the Earl of Rose- Berry, after viewing the Hesketh canvases. Among these were "Chinese Restaurant" (Pic. 5) and "Chinese Mandolin Player” or “Chinese Musicians” (Pic.6). To the De Young Art Museum in San Francisco went his "Chinese Boy and Kite."

(Pic 4) Theodor Wores, “Chinese Candy Seller”, medium, dimensions and present location unknown

(Pic 5) Theodore Wores, “Chinese restaurant”, 1884, oil on canvas, Crocker Art Museum

(Pic 6) Theodore Wores, “Chinese Musicians”, 1884, oil on canvas, private collection

“The Chinese Fishmonger” (Pic. 7) was the first painting he completed after returning to America from Europe, and the dark tones, strong highlights, and expressive brushstrokes reflect his Munich training. Wores struggled to convince Chinese people to pose for his paintings until one of his young assistants, a Chinese student named Ah Gai, accompanied him to translate his requests. In this image, Wores captured the glistening, slimy scales of the fish as they slid from the basket onto the tabletops, so that we could visualize the exotic smells and hubbub of Chinatown’s street markets.

(Pic 7) Theodore Wores, “The Chinese Fishmonger”, 1881, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The journal “Californian” on December 1881 wrote, “The absurd excuse advanced by certain artists who have returned from Europe, that there is nothing to paint, has received at Mr. Wores’s hands a crushing retort. In the unique Chinese world, which preserves its Orientalism intact among us, he has found a fresh and picturesque subject. His picture represents the stall of a Chinese fishmonger”. Another critic noted, “The Chinaman together with the Chinese advertisement on the wall, gives the whole picture a local habitation and a name.”

Interest to the Asian themes, born due to the charm of the Chinese districts and interactions with Chinese people in America, motivated the artist to travel to Japan in 1885, where he stayed for almost three years, living among the Japanese and studying their customs, language, and art. (Pic 8). It’s also worth mentioning that throughout the rest of his career, Wores traveled extensively, painting and sketching in Hawaii, Samoa, Canada, and New Mexico as well as California.

(Pic 8) Theodore Wores (American, 1858-1939). Flower Seller, Tokyo, 1886. Oil on canvas laid on masonite. 26-1/2 x 20 inches

Comparative analysis

For better understanding of the current American artists' attempt to expand the Chinese characters’ influence through a Western scope, one needs the direct observation of the artistic settings of independent eras. Representations of the general image of China, and Chinese people in diverse forms, must be considered through the American art at the time of interpretation and creation.

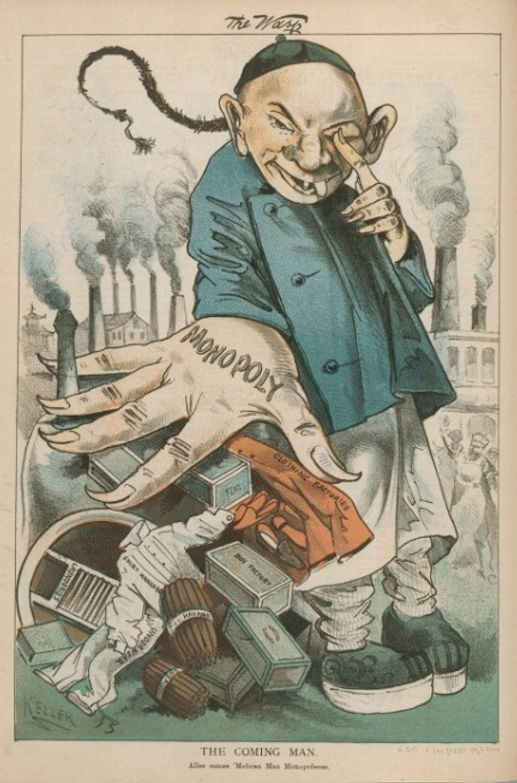

At the end of the 19th century, beyond aesthetics, the art had also become a powerful tool to feed a negative sympathy towards Asian residents of the United States, serving the interests and ambitions of certain political aspirations. Caricatures, political cartoons and illustrations for magazines explicitly conveyed the ethnic image of the Chinese, either as a potential threat for the local “white workers” (Pic 9, 10), able to steal their job opportunities and property, or ugly black collars with the lowest social status, and with physical distortions, deserved to be mocked at ( Pic.11).

(Pic 9) “The Coming Man,” The Wasp, 20 May 1881 in Philip P. Choy, Lorraine Dong, and Marlon K. Hom, Coming Man: 19th Century American Perceptions of the Chinese, p. 91

(Pic 10) A Statue for Our Harbor was published in 1881. It expressed the fear of Chinese immigrants, which led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act 135 years ago.

(Pic 11) 1888 cartoon in the Wasp, a San Francisco magazine, reflecting anti-immigrant sentiment

The evolution of these racist art samples indicated the increase of anti-Asian sentiments all over America. In this context, it is important to mention the Wyoming massacre. On September 2, 1885, 150 American “white” miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming, brutally attacked their Chinese coworkers, killing 28, wounding 15 others and driving several hundred more out of town. Widely blamed for all sorts of societal ills, the Chinese were also attacked by some national politicians who popularised strident slogans like “The Chinese Must Go”, and had helped pass the 1882 law (so-called Chinese Exclusion Act) prohibiting the immigration of Chinese labourers. In this climate of racial hatred, art propagandizing violence against Chinese residents became all too common. “The Chinese Must Go” propaganda was so wide-spread and accepted, that it was adopted by “Magie Washer” advertising campaign, featuring Chinese people as fearful and helpless beings, being kicked off or “washed off” from America by Uncle Sam. (Pic.12).

(Pic 12) An 1886 advertisement for "Magic Washer" detergent- “The Chinese Must Go”

Another cartoon symbolically shows China as an American-conquered land of poverty and famine. While America was featured as a developing, progressive country, drawing parallels between the destroyed symbol of China “The Great Wall,” and the American new-built walls of fortress on the foreground. (Pic.13). As for Wyoming massacre, one of the rare illustrations renders a group of Chinese workers, threatened and desperately fleeing the angry crowd of locals. (Pic.14)

(Pic 13) A cartoon titled, "The Anti-Chinese Wall," showing the "American" wall going up even as the Chinese original wall depicted in the background goes down. Cartoon by Friedrich Grätz (d. 1913) published in Puck, v. 11, no. 264 (29 March 1882)

(Pic 14) An illustration of the 1885 Chinese Massacre appearing in Harper's Magazine. Illustration courtesy of the Rock Springs Historical Museum

Against the background of the anti-Chinese propaganda, even the considerable contribution of the Chinese workers to the Transcontinental Railroad, constructed between 1863-1869 which significantly linked the US from the East to West was ignored or forgotten. Roughly 15.000 Chinese workers had to face dangerous work conditions – accidental explosions, snow, and rock avalanches, which killed hundreds of workers, not to mention frigid weather, yet there few depictions of these monumental contributions of these Chinese workers in the art that was being produced. (Pic. 15) Instead, they are rather additional secondary motifs of the composition (recognized solely by their conical straw hats and traditional hairstyle “Queue”), images that portray the building of the railroad as a pure American achievement.

(Pic 15) "Across the Continent. The snow sheds on the Central Pacific Railroad in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. From a sketch by Joesph Becker." Originally printed in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, Vol. 29, February 6, 1870, p. 346.

As it was noted, a number of Wores’s contemporaries influenced by the European waves of Japanism and Orientalism, have portrayed Western women (Pic. 16), either as patronesses or spouses in Japanese kimono on the background of the Asian-style painted or decorated wall. However, the women although depicted as Asian in origin, had Western facial features and hairstyles, with the artists aiming to show the contrast between East and West in the composition. This was perhaps to display the lavish and cosmopolitan taste either of their own or of their commissioners, with Japanese-inspired fashion and design.

(Pic 16) William Merritt Chase, “Study of a Girl in Japanese Dress” c. 1895, Brooklyn Museum

Thus, Wores work amongst the intolerance towards Chinese immigrants is a progressive, and enlightening crack in the anti-Chinese wall. His view of Chinese culture as its own beautiful subject worth capturing is comparable to the ethnographic and historical significance of Arnold Genthe’s photography, who managed to capture Chinatown lively scenes before the 1906 earthquake. (Pic 17). Two other artists whom Wores knew personally, had similar views and perspectives to his, Paul Frenzeny and Jules Tavernier, created joint sketches on Chinatown of San Francisco (Pic.18). “Harper’s Weekly” in 1877. The paintings are detailed executions of the interior, objects, and figures in national costumes, with a purity that transcends the political and social dialogue of anti-immigration and intolerance.

(Pic 17) Children in SF Chinatown, around 1900. By Arnold Genthe

(Pic 18) Chinese reception in San Francisco, Harper’s Weekly, June 9, 1877

Some sources claim the visits of these artists to Asian headquarters, were another stimulus for Wores to dive into Chinatown themes. Nonetheless, Wores’s oil paintings are independent artworks, beyond magazine illustrations, and are characterized with greater artistic and aesthetic power and quality than many of his counterparts.

Another American prolific painter - William Hahn’s (1829–1887) work, corresponded to the vivid reflections of Chinese scenes of San Francisco by Wores. His “The Market Scene, Sansome Street” (oil on canvas, 60 in. x 96 1/2 in. (152.4 cm x 245.11 cm), Crocker Art Museum, E. B. Crocker Collection, 1872.411) with the presentation of Chinese labourers on the left corner is again an aesthetic view of Chinese themes through the eyes of the curious western artist. Hahn’s oil paintings of the Chinese community in San Francisco preceded Wores series, but the images of the current works are unavailable in open sources.

Conclusion

In the current artistic and historical context, the depictions of Chinese in US by Wores was a breath of the fresh air- an expression of the artist’s personal attitude and point of view on Chinese people and their culture. This influence has become a constant source of inspiration, a notably contrast to the intentionally negative denigration of the Chinese identity through pictures. Wores viewpoint is more appreciable, being compared to his contemporaries’ works on Chinese and Asian themes. Wores’s vision of the Chinese world, helped to form a positive image of Chinese culture and people in the United States, taking Chinese subject matter to new heights. He captured the nature of the Chinese people in their elegance and unique charm, and aesthetically fulfilled life, just like his contemporaries had done with Venice scenes and the Venetians on their European canvases. The American artist turned the simplicity of Chinese daily affairs and leisure into an abundantly-decorated composition (though only ten paintings are known). These paintings are worthy to be observed detail by detail by the American audience of different backgrounds- from art lovers to connoisseurs, commissioners, and amateurs. Wores vision is meant to open American society’s eyes widely to see the Chinese residents in the way they saw themselves, and the pride they felt for their culture.

Figures

Chinese Themes in Early American Art

(3 more canvases by Wores not analyzed in the above article)

Theodore Wores, “San Francisco Chinese maiden”, 19th century, California Historical Society

Theodore Wores (1859-1939) The Old Fisherman 10 x 7 inches, signed, watercolor on paper.

“Golden Parasol”, attributed to Theodore Wores

Esther Anna Hunt: Developing Chinese Themes in American Art

—The market of 19th-20th century American small-scaled handicrafts, postcards and souvenirs with the Asian twist is full of objects titled “Esther Hunt Era”, “a la Esther Hunt”, “Esther Hunt workshop” or “Esther Hunt style”. So who is Esther Hunt and why did she take on Asian, particularly Chinese themes during her career, and why exactly her name became an equivalent to the Chinese subject matters in Early American art?

Despite the fact that the name “Esther Hunt” is still quite popular among art amateurs and collector, there’s little known about this female artist. Hunt was born in Grand Island, Nebraska, in 1875 (Pic.1). Her artistic path as a painter eventually led her to Oriental themes, with a particular focus on portraits and figurines she made from models she met and found in Chinatown of San Francisco. She spent some of her early childhood in Columbus, Nebraska. Her father, Stephen Barton, died in 1879, two years later her mother remarried, and the family went to California. Her stepfather was Captain John A. Frazier, and he took his wife and her children to San Diego County where he acquired 700 acres of land and established the town of Carlsbad. In 1893, the family moved to Los Angeles. It is known that from 1896 to 1900, Esther Hunt was listed in the City Directory as an artist.

In 1901 she enrolled at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art in San Francisco- established in 1871, it is one of the oldest art schools in America. As a means to finance her study the artist started commissioning sketches, watercolour paintings and chalkware busts of local Chinatown children, sending them to a New York dealer who readily sold them. They became popular and widely circulated when she perfected the colour process to make reproductions, reflecting the colourful national costumes of the Asian children. According to some sources, she was also fond of Chinese traditional cuisine.

Making enough money, she traveled to New York City and enrolled in the Art Students League from 1903 to 1905, where she studied with outstanding American artists, such as William Merritt Chase in New York and in Paris for six years. In Paris she mostly learned portraiture. When she had returned from Europe, she had studios in Los Angeles from 1913-1918, San Francisco from 1918 to 1926, Greenwich Village in New York from 1927 to 1931, San Francisco from 1932 to 1945. After a stroke ended her career in 1946, she was taken to the Santa Ana Rest Home in West Orange County where she remained until her death on March 4, 1951.

When she returned to Los Angeles in 1913, she again took up her interest in Chinese subjects and made many painting trips to San Francisco. Settling there in 1918, she devoted most of her attention to the Chinese themes and had a nation-wide market for her paintings, prints, postcards, and coloured ceramic figurines. Hunt was fond of the artistically-created and individually-named "children" she never had in real life.She also did portraits of children in France, beach scenes at Laguna and Native American women and children from the Pomo of northern California. Hunt was a member of the Laguna Beach Art Association, being exhibited along with the American WC Society in 1908, in Detroit Museum in 1909, in Paris Salon, etc.

Her legacy distinguishes with the oils, watercolours, etchings (Pic.2) and coloured ceramic statuettes popular with the general public during her productive years, having been reproduced commercially for postcards, calendars, prints, busts, etc. She paid attention to every detail and each pattern of traditional attires and headgears, forms and design of the shoes, hairstyles of boys and girls, characteristic visage and maquillage of the women, custom-related activities and actions her figures are engaged in. In some cases exchanging the neutral background with the red wallpapers covered with the imitation of Chinese characters or typical Asian surroundings. From the first glance the Chinese women and infants of Hunt’s world are careless and joyful, enjoying their calm life, but there’s always a melancholic vibe hatched from their facial expression or the gloomy background. Perhaps her own loneliness of never having had her own family and children found the indirect expression in her art. Although many independent people, find freedom and meaning beyond traditional roles. However, she’s portraying Chinese little ones with the maternal love and tenderness deeply observing their postures, motions, gestures and mimics. As if once more stressing Chinese features her style and her acknowledgement of Asian culture, Hunt depicted some of the Chinese children with a pure-Chinese attribute: a lantern (Pic.3), a fan (Pic.4), an incense burner (Pic.5), a firecracker (Pic.6), a parasol (Pic.7), worshipping their deities (Pic.8), the others- with a rabbit, a parrot, a cat, a flower-underlining their innocent and dreamy nature. The majority of her works are one-figure compositions, a few genre paintings survived to us, depicting scenes in the temple (Pic.9), children playing with each other, an infant colouring the porcelain jar (Pic.10), mother holding her kids (Pic.11). Throughout her career she experimented with a number of medium: papier-mâché, gypsum, resin, plaster, ceramics and chalkware, composite materials, watercolour and gouache on paper, pastel on paper, oil on board, prints, but never left her favourite Chinese topics.

Nonetheless, Hunt was not the first to take on Chinese themes and undoubtedly not the pioneer in the aspects of decorative female and infant busts and watercolour executions. There were a bunch of influences coming from various sources, intentionally or not, but harmoniously and in commercial meaning successfully blended in Hunt’s art.

1. Arts and Crafts Movement (1860-1920)

The practitioners of the movement strongly believed that the connection forged between the artist and his work through handcraft was the key to producing both human fulfillment and beautiful items. Arts & Crafts artists are largely associated with the vast range of the decorative arts, in fact uniting all the arts within the decoration of the interior and exterior of a dwelling. The system of patterns and florid motifs catching the eye in Hunt’s statuettes, the decorative function and essence of her works make her legacy possible to be explored close to the current movement. Furthermore, Hunt’s busts were designated to be a part of an inner design, being comprehended as a carry-home object.

2. Art Nouveau was an international style of art popular between 1890 and 1910, reaching its summit in Paris, where Hunt studied and was familiar with. The parallels of the distinctive features of Hunt’s manner and Art Nouveau concepts intersected in the following outlooks.

A. Breaking down the traditional distinction between fine arts (especially painting and sculpture) and applied arts, highlighting decorative character

B. Use of modern materials, including various sorts and wares of ceramics and papier-mâché,

C. Idealised, feminine and attractive female figures in paintings and in the form of sculptural busts, specified with the lavish jewellery, clothes and detailed hair decorations, just like most of the Hunt’s Chinese women. They are rather general images and imaginative, non-real personages with perfected facial features, perceived more as a symbol, embodiment of exquisite taste and decor.

3. Aesthetic movement and Aestheticians (1860-1900s)

There was another powerful movement covering America that flooded in from Europe, mainly England. Aestheticians attracting more and more followers and contemplators from the artistic elite, also determined with the depiction of female characters, rather creating a sense of mood of beauty to please the eye, than a narrative with in-depth didactic function. Analysing the formal and contextual qualities of Hunt’s works, we’re keen to believe that there are similarities between her style and Aestheticians' concepts, resting our thesis on the circumstances described below:

a. Oriental techniques, themes, methods, manners due to their decorative features were widely adopted by Aestheticians, as well as by Hunt, though the primary source of her influence in terms of Chinese themes came directly from her local Chinatown.

b. The desire to create "art for art's sake" and to exalt taste, the pursuit of beauty, and self-expression over moral expectations and restrictive conformity

The years of Hunt’s career coincide with the birth and dissemination of the key movements breaking the boundaries between the high and the low art, the fine arts and the applied arts, as well as partially implying media, techniques, compositional details originating in Asia, thus providing the motifs and notions to the generation of her individual artistic language. It is worth mentioning that the first Chinese immigrants entering the United States were mostly males, the majority of whom began arriving in 1848. Moreover, the Page Act of 1875 prohibited the entry of Chinese women to America, so the delicate Chinese female busts of this American artist perhaps were mostly the product of her imagination decorated with the floral and vegetal ornamental and colourful jewellery-like patterns, typical for Art Nouveau busts, close to female characters preferred by Aestheticians and ornating leitmotifs floating in Arts and Crafts movement.

Speaking of the figurines of cute children, here we see other types of layers of cultural references.

4. Kewpie baby

In the early 20th century a New York-based writer and illustrator Rose O’Neill conceptualised a cartoon image of a cherub-faced, cupid-like character called “Kewpie” . Gaining popularity she began to sell their paper doll versions, afterwards, developing a line of lovely dolls and figurines in partnership with Geo. Borgfeldt & Co.. Esther Hunt, being a member of the renown artistic clubs and associations, befriended well-known artists of her time, was certainly aware of this wide-spread infant character. The parallels between these two female artists’ creations is quite obvious especially comparing the Kewpie doll sucking his finger with the Hunt’s bust of a Chinese kid with the same gesture. (Pic.12) However, Kewpie statuettes could not be considered portraits, but in case of Hunt’s infant busts and figurines, most of them seem to be done from real models of Chinatown, their expressions, gestures, appearance do not bear strong resemblance to one another and they are not standardised, though there were a couple of repeated types Hunt reproduced either herself or with the assistance of her students.

5. Chinese Big Afu and Wuxi babies

The clay figurines of babies in Chinese culture could be traced back to the Song dynasty (960-1279): children playing with each other was the common theme related to the Chinese customs and festivals. There are chubby and merry baby statuettes called “Muhura” connected with Buddhism and perceived as the son of Buddha Sakyamuni, who, after the enlightenment, made Muhura one of his disciples. The cult of this infant deity was wide-spread and there were even certain workshops specialised in executing folk ceramic figurines of Muhura, holding a lotus leaf, used in various fests. From the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) the plumply, rose-cheeked, folk-dressed smiling baby handmade figurines, from mould and resin became a trademark of Wuxi city (Chinese: 无锡, Jiangsu province, Eastern China). Diverse versions with different functions were in use, among them in great request was and still is “Big Afu” (Da A Fu, 大阿福 in Chinese) - clay figurine of a baby with a small animal in his arms, symbolising good fortune and fertility. Besides, infant images were one of the major themes in Chinese paper cutting art. All the above-mentioned folk art small-sized objects were circulating in San Francisco Chinatown stores particularly during the Chinese New Year festival, so Esther Hunt had all the chances to see them and be inspired by them while making sketches in the Chinese headquarter. The media, tiny measures, concept and formal characteristics have close links, anyway, Hunt rather preferred busts and added her own Western spot to this form of art.

6. American artists executing Chinese subjects throughout the positive light

The most remarkable one is apparently Theodore Wores (1859-1939), one of the pioneers preceding her a decade and more, making Chinese themes one of the cornerstone of his career. William Merritt Chase with whom she studied at Paris, was known for his exquisite Western women portraits in Japanese kimono, surrounded by Oriental objects. There are two artists featuring Chinese children of San Francisco Chinese quarters in their works- Frederick Bauer (1890s, “Chinese children”, oil on canvas, E.Hughes collection) and Louise D. Brown (undated, probably early 20th century, Chinatown scene) capturing Chinese districts’ views and their inhabitants close to Hunt’s style. Different artistic groups and clubs in San Francisco (Bohemian club) and Los Angeles have become a place of gatherings of intellectuals and representatives of the cultural sphere, many of them explicitly or implicitly representing Asian-related subjects, media or concepts in their works. Therefore, Asian subject matters in various visual depictions and forms were boiled in American art circles and in Europe, where she studied, as well, there’s no wonder why she tried herself in Chinese themes either.

7. Boom of postcard culture

In 1861 the US Congress passed an act that allowed privately printed cards, weighing one ounce or under, to be sent in the mail. That same year John P. Charlton copyrighted the first postcard in America. The US golden age of postcards is commonly defined as starting around 1905, peaking between 1907 and 1910, and ending by World War I, appropriate to the prolific years in the career of Esther Hunt. Demand for postcards increased, government restrictions on production loosened, and technological advances (in photography, printing, and mass production) made the boom possible. Scenic landscapes, portraits, exhibitions, humorous scenes or even current events were quickly printed in postcards shortly after taking place. The many surviving examples of such postcards tell a vivid picture of the time. In San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York, where the Chinese immigrants have lived in large numbers, publishers started the process of creating and selling the postcards featuring Chinese families, children, views from Chinatown, representing them as a peculiar trait of the city, displaying people with their emphasised cultural identity, habitudes, customs and lifestyle mostly in a good light, Chinatown- a place worth to visit and get acquainted with those people. It’s not known to which publishing companies Hunt cooperated with, but a significant number of brightly-coloured postcard images of Chinese residents widely-spread in the early 1900s speaks on the matter that she was “in the right place at the right time”. She created and designed stereotyped images of Chinese infants in their vividly coloured garments with an Asian attribute communicating with the viewer by a sweet gaze, heavily fitting the standards of the illustrations of postcards’ rising culture and possible to use as a postcard image instead of a photograph.

The unprecedented quantity of the postcards, prints, original and even non-original watercolour and gouache paintings of Chinese children, finally, wide range of the Chinese busts reached to nowadays and also some advertising notes in early 20th century American newspapers calling for purchasing the female “Chinese heads” of Hunt as a “Christmas gift” (Pic.13) leave no doubts that Esther Anna Hunt rose to fame at least in the 1920s. To the truthfulness of this theory speaks the fact that some of her works are signed also by other artists and that her intimate manner of depiction of females and infants of Asian origin was in demand and influenced many other artists and designers. On the other hand, these particular circumstances make the attribution and authentication of her works extremely complicated, also considering the fact that a great number of busts and watercolours are unsigned.

Though there’s nothing recorded on her collaborations with other artists, in accordance with a pair of the Chinese-style bookends one of them signed by Hunt, the other- by Leon Fighiera (1881-1938) (Pic. 14), it would be logical to assume that a number of Hunt-designed busts were made at the workshop of this Italian artist, as by 1912 he had a studio in Los Angeles where he produced busts, statues and bas-relief plaques. Besides, already in 1922 he relocated to San Francisco running the Mont Martre Art School and at the same time producing “statuettes of Chinese children for Esther Hunt”. There are a number of busts, chalkware plaques and small decorative items signed by Fighiera made in 1920s (majority of them in 1925) sold or still available in art auctions.

Among the followers of Hunt’s busts trend was another Italian artist, Joe Celona. The American art dealer, art collector and author of biographical records of Californian artists Edan Milton Hughes in his “Artists in California, 1786-1940” publication includes scarce information about this artist. He was born in Italy in 1860. By 1918 Celona had a studio in Los Angeles where he produced chalkware busts, bookends and plaques. He died there on Jan. 13, 1933. It’s unclear when and how Celona met Hunt, anyway, taking into account the fact that several statuettes and busts are signed by the current three artists- Hunt, Fighiera and Celona (Pic.15), probably the latter came across Esther Hunt at Fighiera’s workshop in 1920s and for awhile they all worked together in mass production of these art objects.

Analysing a pair of the Asian female busts created and signed by Hunt, one can notice another name next to her: “PLUMBLOSSOM. ''Grace Nicholson/...Pasadena, Calif.’' (Pic.16) Grace Nicholson (1877 – 1948) was an American art collector and art dealer, specialising in Native American and Chinese handicrafts. The space she originally designed for her shop is now home to the USC Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, California. Hunt’s fame reached other cities of California, and art collectors, like Nicholson were keen to acquire at least a couple of her works.

It’s worth mentioning that among Hunt’s adherents was even a resident of San Francisco Chinatown: WyLog Fong. Born in San Francisco in the 1890s, the son of a tailor, Fong spent his childhood in the city's pre-Earthquake "Old Chinatown" - where he witnessed the street scenes he later idealised in his paintings. Although there’s no record whether these two knew each other personally, it’s known that Fong was in Los Angeles for a while and then returned back to San Francisco, they could have met in both places. He was described as a “sidewalk pastel portrait artist” in Los Angeles’ Chinatown. The West Coast Engraving Company slips him “a Chinese Artist of the Younger generation whose work is attracting widespread attention”, contracting with him to produce Chinatown sketches which were widely marketed as colour prints throughout the 1920s, particularly popular in California department stores. Returning to San Francisco, where his name was relatively known, Fong also did magazine illustrations and portrait paintings on velvet. (Pic.17) The protagonists of his small-sized works are his compatriots from the Chinese quarters, displayed manoeuverly in close proximity with Hunt’s personages.

Hunt has nowadays followers as well, there are artists who are using her antique busts to make ready-made objects or functional items, utilitarian design samples, lamps, matching them with the ancient textiles and embroidered fabrics. (Pic.18)

Which events and occasions made Hunt’s art far-famed all over America?

A. The 1920s is the decade when America's economy grew 42%. Mass production spread new consumer goods into every household and the growing middle class was willing and able to purchase widely available consumer products, as well as souvenirs and decorative items for reliable prices.

B. Although the 1882 law (so-called Chinese Exclusion Act) prohibiting the immigration of Chinese labourers did not expire, in the early 20th century view shifted a little to the direction of toleration and growing interest in Chinese food, culture, folk art. Photography of Chinese quarters in the positive light, Chinese cookbooks authored by American women, even novels and short stories either discovering peculiarities of Chinese lifestyle or telling the true-based love story of a Chinese man and a Western woman were circulating in crowded cities of prospering America. The notorious cartoons by Thomas Nast harbouring antipathy towards Chinese immigrants and China were partially outmoded. At the end of the 19th century the World's Transportation Commission organised a trip across the world with the purpose to document traditional and novel forms of transportation internationally, as well as the local environment and people. Commission members, among them prominent photographer William Henry Jackson (1843-1942), also visited China, where Jackson took hundreds of photos of ancient Chinese streets, architecture, women, children, etc., increasing awareness of them. It’s noteworthy that after the 1911 revolution in China more foreigners, including Americans, had an opportunity to travel there for various intentions. American art dealers and connoisseurs were enthusiastic in holding exhibitions of Chinese traditional art and artists in California. The current new-born drifts were patently pronounced in San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake, when wealthy merchants of Chinese origin joined their efforts in rebuilding the Chinese quarter, in order to turn it into “an exotic wonderland for non-Chinese visitors”.

The Harlem Renaissance (c.1918) - the highly influential African American cultural awakening in visual and creative arts undoubtedly changed the attitude to the national minorities and immigrants and their culture, additionally indirectly affecting the public perception of the residents of Chinese origin.

It’s also worth mentioning that the very nature of the World War called into question the West’s perception of itself as “civilised.” Small wonder, then, that many in the United States and Europe began to question the values and assumptions of Western civilisation, turning their eyes to the Oriental lands.

Thus, the more and less positive image of Chinese ethnicity being formed in the American society in the first decades of the 20th century made the fertile ground for the rise and success of Esther Hunt’s artistic concepts.

C. Busts and postcards were not a kind of art for museums and wealthy patrons, they directly targeted the public demands and average expectations of consumers, that’s why they are simple to perceive, colourful for the eye, bright palette was meant to attract more viewers and they were lovely enough to be eager to purchase and generalised to fit any type of apartment and environment at that time.

Why is this artist significant within the context of her age and from our nowadays perspective as well?

a. Esther Anna Hunt represents a rare female gaze and female approach to the Asian themes in Early American, particularly Californian art, mainly focusing on infants and female characters, being a pioneer in that particular aspect.

b. Hunt spontaneously proved that America of her times has local picturesque sites and interesting models to be captured by artists, so there’s no need to seek inspiration abroad.

c. She gave impetus to the Chinese subject matter, popularising it among masses and made it recognisable from the first glance. The artist created generalised images of a Chinese woman and a Chinese child in their colourful folk attires, a mass-perceived type, which were symbols of China and Chinese identity, being appropriate enough for reproduction on commercial items of diverse purposes. She formed another, fundamentally different public image of Chinese immigrants at the turn of the century, as if rebelling against representations of Chinese natives in the 19th century American press and illustrative art as black collars, in hard living conditions or ugly creatures deserved to be mocked at. On the other hand, she turned Chinese themed-objects in not only works of art made for the limited ones and special environments, not only for wealthy patrons, amateurs obsessed with Orientalism or collectors and galleries of Asian culture, but wide audiences of the American society to contemplate and to be ready to purchase as a gift or a souvenir. She showed up that despite the fact that Chinese immigrants differentiate from Western people, but those distinctive features are worth to explore, appreciate and interpret, and exactly that argument turns her art into an indicator of the taste to Orientalism and a demand of Asian-inspired items in American society of the early 20th century.

The primary reason for “falling out of fashion” of this type of Asian-inspired art with emphasised decorative character is the Great Depression. The Roaring Twenties screeched to a halt on October 29, 1929, also known as Black Tuesday, when the collapse of stock prices on Wall Street ushered in the period of US history known as the Great Depression, having severely affected the cultural world of America. Both Hunt and artists with whom she collaborated and young generation of painters like Fong who, evolving her approach of “Chinese genre”, started to take portrait commissions, drawing landscapes, still life with cheaper materials. Social realism, also known as socio-realism, became an important art movement in 1930s, displaying social and racial injustice and economic hardship through unvarnished pictures of life's struggles, portraying working-class activities as heroic.The Federal Art Project of America, created in 1935 as part of the Work Progress Administration, directly funded visual artists and provided posters for other agencies, giving preferences to socio-realism and modern movements in art. The general mission of the artists’ was now considered reflecting the life of a common American, with a particular focus on people meeting the challenges of the Great Depression. The government also paid to abstract expressionists, as American-innovated and established art movement, so the elegant and lovely Chinese busts, as well as delicate genre paintings demonstrating tranquil life of Chinatown were in strong contrast with both the social realistic concepts and non-figurative modern art, that’s why they simply became out of trends with a few commissioners and decreased public demand.

Figures

Esther Anna Hunt:

Developing Chinese Themes in American Art